Let's talk about young eels. If you're here, you've probably heard the terms "glass eel" or "elver" thrown around, maybe in a news article about crazy prices or conservation worries. It's a weird little corner of the natural world that feels almost like a secret. I got pulled into it a few years back after a trip to a coastal market, and honestly, the more I learned, the more fascinated I became. It's not just about fishing; it's about one of the most bizarre animal journeys on the planet. So, what exactly is a young eel? It's not a simple answer. It's a phase, a temporary form in a life story that's still full of mysteries even for scientists. We're talking about a creature that breeds in the middle of an ocean, then its babies ride currents for months to reach coasts, transforming along the way. The term "young eel" generally covers two specific stages right after they hit freshwater: the see-through glass eel and the slightly more developed, pigmented elver. This guide is my attempt to unpack all of it—the science, the fishery, the controversy, and the sheer wonder of it. Forget dry textbooks; let's just dig in. Quick clarification: When people say "baby eel," they're almost always talking about the glass eel or elver stage. True eel larvae, called leptocephali, are flat and leaf-like and live out in the open ocean. By the time they're caught by fishermen, they've already morphed into the tiny, transparent eels we're discussing here. To understand the young eel, you have to start with the big picture. Eels like the European (Anguilla anguilla) or American (Anguilla rostrata) species are catadromous. That's a fancy word meaning they live most of their lives in freshwater but swim thousands of miles out to sea to spawn and die. The Sargasso Sea, a region in the North Atlantic, is the famous (and still not fully understood) breeding ground. The adults vanish into the deep, and their eggs hatch into those leptocephali larvae. These larvae drift for months, maybe even over a year, on ocean currents. When they finally approach the continental shelves, something remarkable happens. They undergo a metamorphosis. The leaf-like larva shrinks, becomes cylindrical, and transforms into a young eel in its glass eel stage. They're about 2-3 inches long, completely transparent (you can see their spine and organs), and they're finally ready to enter freshwater. This transition is mind-blowing. They go from a saltwater ocean drifters to freshwater seekers. Their bodies change function. It's a physiological marathon. And they arrive in massive, pulsing runs, usually on dark, moonless nights during winter and spring, guided by tide and scent. That's when people meet them. This trips a lot of people up. Are they the same thing? Almost, but not quite. It's a progression. Think of it like this: a glass eel is a fresh arrival, still figuring out the new environment. An elver has gotten its bearings and is now on a mission to move inland. Both are critically vulnerable points in the eel's life cycle. This is where things get practical, and contentious. The glass eel fishery is high-stakes. Why? Because these young eels are the seed stock for the entire eel aquaculture industry, especially in Asia. They can't breed eels in captivity reliably at a commercial scale (yet). So, farms need wild-caught glass eels to grow out to market size. The methods are low-tech but require specific knowledge. Fishing usually happens at night during incoming tides when the eels are riding the water into the rivers. The main gear: The catch is then sorted, often by hand, to remove debris and other species. The live glass eels are kept in oxygenated water. From here, their fate diverges. Some may be sold for direct consumption (a rare, seasonal delicacy in places like Spain or Japan). But the vast majority enter a global supply chain. They are flown live, in special chilled packages, to eel farms, primarily in China. The value is astonishing—at peak prices, a single kilogram of glass eels (containing thousands of individuals) can be worth tens of thousands of dollars. It's been called "glass gold." Let's be real: This fishery is a flashpoint. The high value has led to poaching and illegal trade, which is a massive problem for conservation. Even legal fishing is heavily regulated with strict quotas, seasons, and licensing because eel populations have crashed. The IUCN Red List lists the European eel as Critically Endangered. Relying on a critically endangered species' babies to supply a global food industry is, to put it mildly, a tricky and unsustainable situation. Many argue the fishery should be closed entirely until stocks recover. It helps to see the whole journey laid out. Here’s where our focus—the young eel—fits into the grand, weird scheme. See that? The young eel stages (glass eel and elver) are just a brief window. But it's the only window where new recruits enter the continental population. If this pipeline gets blocked or over-exploited, the entire population downstream collapses. That's the core of the conservation panic. Okay, so why this massive global trade? Why not just catch adult eels? The answer is on your sushi plate. Unagi (grilled eel) is hugely popular, especially in Japan. Wild adult eel populations can't meet the demand. Aquaculture stepped in. But here's the kicker: we've mastered growing eels from the young eel stage to adulthood in ponds and tanks. We have not mastered getting them to reproduce reliably in captivity. Their spawning triggers are too complex, tied to deep-ocean pressures, hormones, and journeys we can't replicate in a tank. So, the entire multi-billion dollar eel farming industry rests on a paradox. It's a form of aquaculture that is 100% dependent on a wild-caught seed. Every single farmed eel you eat started its life as a wild glass eel scooped from a river in Maine, Portugal, or elsewhere. This makes the supply chain incredibly sensitive. A bad year for glass eel recruitment means shortages and skyrocketing prices for farms, which eventually hits restaurant menus. It's a strange model. Most farmed fish, like salmon or tilapia, are bred in hatcheries. Eel farming is more like "eel ranching"—catching wild babies and fattening them up. This creates intense pressure on those wild glass eel populations. Scientists and groups like the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) have flagged this as a major sustainability issue for decades. The search for a solution is frantic. Research labs are working tirelessly to crack the code of closed-cycle eel reproduction. There have been successes—scientists have induced spawning and produced larvae that live for a short while. But getting them to survive through the fragile leptocephali stage and metamorphose into a healthy glass eel at a commercial scale? That's the multi-million dollar holy grail. Whoever figures it out could revolutionize the industry and take the pressure off wild young eels. But we're not there yet. You can't talk about young eels without getting into the messy, worrying conservation story. Eel populations, particularly the European and Japanese species, have plummeted. Estimates suggest European eel numbers are maybe 5-10% of what they were in the 1970s. It's a perfect storm of threats: The regulatory response has been a patchwork. The European eel is under strict management plans. CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) lists it, controlling international trade. Many countries have closed seasons, catch limits, and bans on exporting glass eels outside the EU. The United States, through agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, also monitors and regulates the fishery, though the American eel is not currently listed as endangered. But enforcement is tough. The high value fuels a black market. Illegal catches are often smuggled and mixed with legal ones, making a mockery of quotas. From my reading and conversations, it feels like a constant cat-and-mouse game between authorities and poachers. What can an ordinary person do? Be an informed consumer. If you eat eel, ask where it's from. Support restaurants and suppliers that are transparent about their sourcing. Better yet, maybe give unagi a break until the industry finds a truly sustainable path. The pressure from consumers can push for change faster than slow-moving regulations sometimes. I get a lot of the same questions when I nerd out about this topic. Here are the big ones. Yes, but it's a niche thing. In parts of northern Spain (like the Basque Country), "angulas" are a celebrated and very expensive delicacy. Traditionally, they're sautéed in olive oil with garlic and chili. What you often find in restaurants now, though, are surimi-based imitations called "gulas" because real glass eels are so costly and regulated. In Japan, they may be served as a topping or in a dish called "noresore." The taste is mild, a bit salty, with a unique soft texture. It's delicate. They need cold, clean, highly oxygenated water. Stress kills them quickly. In transit to farms, they're packed in special insulated boxes with chilled water and pure oxygen. The goal is to slow their metabolism for the long flight. Mortality during transport is a significant economic loss and an animal welfare concern. In common parlance, yes. When a news report says "baby eels worth $2,000 a pound," they mean glass eels. Scientifically, the true "baby" or larval stage is the leptocephalus, which you'll never see unless you're on a research vessel in the Atlantic. The transparency (lack of pigment) in the glass eel stage is part of the metamorphosis from the ocean-going larva. It's a transitional form. The pigment cells develop later as they prepare for life in sunlit rivers, providing camouflage against predators. Being see-through in the open ocean might have offered some advantage, too—making them harder to spot. That's the million-dollar question. The future likely depends on a few things: 1) Stricter, smarter global enforcement against illegal fishing and trade. 2) Major investments in habitat restoration, like building eel ladders around dams. 3) A breakthrough in closed-cycle aquaculture. If we can farm them from egg to plate, the pressure on wild young eels vanishes. Until then, it's a managed, high-risk resource. Personally, I think the fishery in its current form is on borrowed time unless stocks show real, sustained recovery—which hasn't happened yet. Writing about young eels always leaves me with mixed feelings. On one hand, their biological story is a masterpiece of evolution—a transoceanic mystery that we're still piecing together. It's awe-inspiring. On the other hand, the human side of the story is a classic tale of high demand meeting a fragile, slow-to-reproduce resource. It's a collision course. The tiny glass eel, this almost invisible creature, sits at the center of a global web connecting oceanography, river ecology, international trade, gourmet cuisine, and conservation law. It's more than just a "baby eel." It's a litmus test for how we manage our shared natural resources in a connected world. If you take one thing away from this, let it be this: the next time you see a mention of "glass eels" or hear about their price, you'll know there's a whole ocean of story behind those two words. It's a story worth understanding, because the fate of these young eels is, in a way, a reflection of our own choices.Key Insights

The Incredible Journey: From Ocean Mystery to River Resident

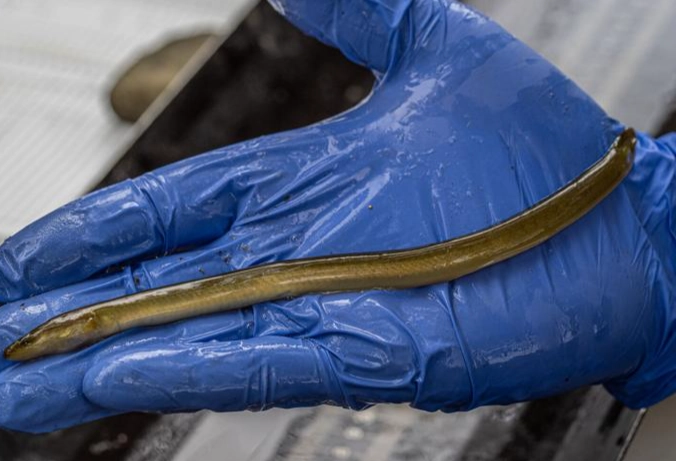

Glass Eel vs. Elver: Spotting the Difference

How Are Young Eels Caught? A Look at the Fishery

The Lifecycle in a Table: From Egg to Adult

Life Stage Name Where It Lives Key Characteristics Duration 1. Egg & Early Larva Leptocephali Sargasso Sea / Open Ocean Flat, transparent, leaf-shaped body. Carries energy for the long drift. Several months to over a year 2. Coastal Metamorphosis Glass Eel (Young Eel) Ocean-Continent Shelf, Estuaries Cylindrical, transparent, ~2-3 inches. Undergoing physiological change to enter freshwater. Weeks to a few months 3. River Entry & Upstream Migration Elver (Young Eel) Estuaries, Lower Rivers Pigmented (brown/green), stronger, begins active feeding and upstream movement. Months to a few years 4. Growth Phase Yellow Eel Freshwater Rivers, Lakes, Wetlands Fully pigmented, bottom-dwelling, feeding and growing. This is the long "resident" phase. 5 to 20+ years 5. Sexual Maturation & Migration Silver Eel Transitioning from Freshwater to Ocean Eyes enlarge, belly turns silver, digestive system degenerates. Prepares for non-stop ocean migration back to spawn. Months (during migration)

Why Are Young Eels So Valuable? The Aquaculture Link

Conservation: The Elephant in the Room

Frequently Asked Questions About Young Eels

Can you eat glass eels?

How do you keep glass eels alive?

Are young eels the same as baby eels?

Why are they transparent?

Is there a future for eel fishing?

Final Thoughts

The arrival of glass eels is one of nature's great, silent migrations. On a quiet night at the right estuary, you might see thousands of these nearly invisible creatures, each having traveled an oceanic odyssey we can barely map, now wriggling into the river mouth. It's humbling.

Comment