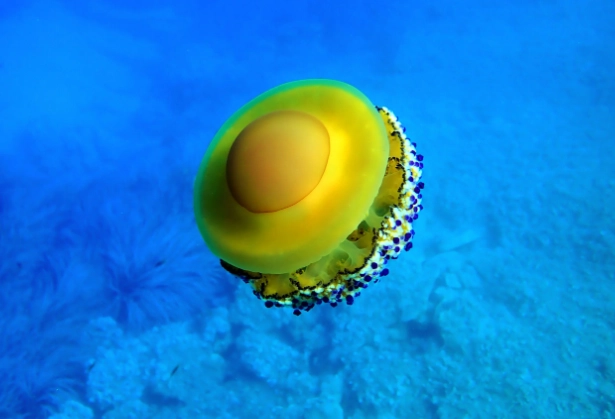

Okay, let's be honest. When you think of jellyfish, you probably picture those graceful, pulsing blobs drifting in the ocean, maybe with a slight sting. But have you ever stopped to wonder where they come from? I mean, they don't just appear out of nowhere. The story starts with something incredibly tiny and often overlooked: jellyfish eggs in water. It's a world most of us never see, and honestly, it's way more fascinating than I initially thought. I remember the first time I saw what I thought were jellyfish eggs in water during a night dive. It was just a cloudy, almost milky patch. My guide pointed it out, and my mind was blown. That vague cloud was the starting point for hundreds, maybe thousands, of future jellies. That moment got me hooked, and I've been digging into the science ever since. So, if you're curious about what these eggs look like, how they survive, and why they matter, you're in the right place. This isn't just a dry biology lesson; it's a look into one of the ocean's most common yet secretive processes. This is the first question everyone has, and the answer is: it depends, and they're usually not what you expect. Searching for jellyfish eggs in water with the naked eye is like looking for a single grain of sand on a beach. You need to know what you're looking at. For many common jellyfish species, the process starts internally. Females brood fertilized eggs within their body, often in special pouches, and release tiny larval forms called planulae. So, you won't see eggs floating freely. What you might see is the result: a cloudy, soupy-looking mass in the water near a female jellyfish. This mass is comprised of thousands of these planulae. They look like specks of dust or fine pepper suspended in the sea. Not exactly the classic "egg" image, right? Other species, like the Moon Jellyfish (Aurelia aurita), take a different route. Females catch sperm released by males and then fertilize their eggs internally. They'll then carry the developing embryos on their oral arms—those frilly bits under the bell—for a while. If you see a Moon Jelly with little clumps or a grainy texture on its arms, you're looking at its future offspring! Eventually, these develop into planulae and drop off. Then there are species that do broadcast spawning, releasing both eggs and sperm directly into the water column. In this case, the actual jellyfish eggs in water are microscopic spheres, utterly invisible unless you have a plankton net and a microscope. What might be visible from a boat or shore during a massive spawning event is a slight discoloration of the water—a milky or pinkish hue. So, to sum it up visually: This is where it gets really cool. Jellyfish have a lifecycle called "alternation of generations," which sounds like a sci-fi novel but is just brilliant biology. The jellyfish eggs in water (or the planula that comes from them) is just the opening act. Once an egg is fertilized—whether inside the female or out in the open water—it develops into that tiny, hairy, pear-shaped planula larva. This little guy has one job: swim. It uses tiny hair-like cilia to move, but it's mostly at the mercy of currents. Its goal isn't to grow into a jellyfish immediately. No, its goal is to find a nice, solid spot to settle down. A rock, a shell, a piece of dock, even the underside of a boat. This phase can last from hours to days. This is the stage most people don't know about, and it's arguably the most important. When the planula finds its spot, it attaches head-first and transforms into a polyp. It looks like a tiny sea anemone or a little stalk with tentacles. It's not a baby jellyfish; it's a completely different life form. This polyp is a feeding machine, catching plankton. And here's the kicker: it can live like this for years. It's essentially immortal under the right conditions, and it can even clone itself, creating whole colonies of genetically identical polyps. This is how jellyfish populations can explode seemingly overnight—the polyp "factory" on the seafloor has been stockpiling. When conditions are right (often triggered by water temperature, food availability, or daylight changes), the polyp undergoes a process called strobilation. It basically segments itself, like a stack of tiny plates. Each of these plates pinches off and swims away as an ephyra, a tiny, star-shaped juvenile jellyfish. The ephyra grows and gradually takes on the familiar bell shape of an adult medusa—the form we recognize as a jellyfish. Only now, as a mature adult, will it produce eggs or sperm, and the whole cycle begins again. It's a bit mind-blowing, right? The creature we fear or admire is just one phase in a much longer, stranger story. The presence of jellyfish eggs in water near you hints at this entire hidden drama happening on docks, boat hulls, and the seafloor below. You hear about "jellyfish blooms" all the time—those massive swarms that can clog fishing nets, shut down power plants, and take over beaches. Where do they come from? The answer lies in the efficiency of that life cycle, starting with the production and survival of those initial stages. Human activities are basically creating a perfect world for jellyfish polyps. Here’s how: The polyp stage is the key. A single, well-established polyp colony can pump out thousands of ephyrae. So, when you see a bloom, you're not just seeing a bunch of adults that gathered; you're seeing the highly successful output of a vast, hidden network of polyps that benefited from the conditions we've created. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has extensive research on how changing ocean conditions contribute to these phenomena, which you can explore in their resource collection on ocean changes. Let's get practical. You're at the beach, on a boat, or looking at your saltwater aquarium. You see something weird. Could it be jellyfish eggs in water? Here’s a quick breakdown of what else it might be. The best way to know for sure? If you're curious and have access, a simple plankton net tow can collect samples. Viewing them under a cheap microscope or even a strong magnifying glass can reveal a whole new universe. The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and similar marine labs have amazing public resources and images of plankton that can help with identification. If you're a saltwater aquarium hobbyist, the sudden appearance of tiny jellies or polyps can be a surprise. Most common is the dreaded "hydroid jellyfish," which are not true jellies but close relatives. They look like tiny white flowers on your glass or rock, and their free-swimming medusae are pinhead-sized bells. True jellyfish eggs in water systems are rare because most aquarium jellyfish are cultured from polyps in specialized labs. However, if you have live rock or corals from the ocean, it's possible you've imported a hidden polyp. Seeing a small, strange jellyfish appear is a sign that polyp is now active. Is it a problem? For a standard reef or fish tank, yes. Most jellyfish, even small ones, have stinging cells that can irritate or stress fish and corals. They can also compete for food. For a dedicated jellyfish tank (a kreisel or laminar flow tank), it's the goal! But raising jellyfish from this stage is notoriously difficult. They require a constant supply of microscopic food like rotifers or newly hatched brine shrimp, and extremely gentle water flow to prevent them from being sucked into filters. My own attempt at raising some Moon Jelly ephyrae I found was a humbling failure. They require meticulous, daily care. Unless you're specifically set up for it and ready for a major commitment, treating an unexpected jellyfish outbreak as a pest is the practical approach. Good tank hygiene, careful sourcing of live rock, and predators like certain wrasses can help control polyp populations. Let's tackle some of the specific questions people type into Google. These are the things I wanted to know when I started. Almost never. The stinging cells (nematocysts) of most jellyfish aren't developed or potent enough in the egg, planula, or ephyra stages to penetrate human skin. You could swim through a cloud of planulae and likely feel nothing. The danger, if any, comes from being near the adult medusae that produced them. That said, it's always wise to avoid any unidentified cloudy patches in areas known for highly toxic jellyfish, as a precaution. But the eggs themselves? Not a threat. There's no single answer, as it varies wildly by species and conditions. But let's take a common example like the Moon Jellyfish: So, from the moment of fertilization, the fastest route to a recognizable adult might be a couple of months. But the polyp can press "pause" for a very, very long time, making the total potential timeline years long. This complexity is why it's so hard to predict blooms simply by looking for jellyfish eggs in water. This one comes up surprisingly often. While adult jellyfish are a common food in some Asian cuisines (usually desalinated and served in salads), their eggs are not a known commercial food item. They are microscopic, incredibly fragile, and would be nearly impossible to harvest in any meaningful quantity. So, no, you won't find "jellyfish caviar" on the menu. The nutritional focus would be negligible anyway. Stick to the prepared adult bells if you're curious about the culinary experience. This is a crucial part of the ecosystem balance. Despite their defenses, jellyfish early life stages are food for many creatures: The fact that polyps have so few dedicated predators is one reason they can persist and build up their numbers. Organizations like the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) use remotely operated vehicles to study these deep-sea and micro-interactions, revealing how interconnected these food webs are. You might think, "Okay, cool science lesson, but why does this matter to me?" Understanding that jellyfish start as jellyfish eggs in water and, more importantly, as polyps, changes how we see our oceans. Jellyfish are powerful indicator species. A surge in their populations is a red flag, a sign of fundamental shifts in the marine environment—overfishing, pollution, warming, and habitat change. For coastal communities, predicting blooms can help protect fisheries, tourism, and infrastructure (like power plant intakes). The key to prediction isn't just monitoring adults; it's understanding and, where possible, monitoring the polyp populations on artificial structures. Some places are now experimenting with "polyp hotels"—easily removable surfaces that can be checked and cleaned to control local polyp numbers. On a personal level, it just makes experiencing the ocean richer. Next time you're by the sea, you'll know there's an entire, mostly invisible world of tiny swimmers and hidden polyps churning out the graceful, pulsing jellies you see on the surface. That cloudy patch near the dock? It might just be the nursery. That weird little bump on the piling? Could be a polyp factory. It adds a whole new layer of mystery and appreciation. So, the next time someone mentions jellyfish, you can move beyond "they sting" and dive into the real story. It's a story that begins with something almost nothing: a microscopic egg or larva adrift in a vast ocean, following a survival playbook that's millions of years old and incredibly resilient. And in today's changing seas, that resilience is writing a new chapter, one we're all a part of.In This Article

What Do Jellyfish Eggs Actually Look Like in the Water?

The Wild and Complex Jellyfish Life Cycle: It's Not Just Egg to Adult

From Fertilization to Planula: The First Swim

The Secret, Sedentary Stage: The Polyp

Think of the polyp as the ultimate survival bunker. It's tough, it can wait out bad conditions, and it can make copies of itself. The free-swimming jellyfish is just its way of spreading genes far and wide.

Think of the polyp as the ultimate survival bunker. It's tough, it can wait out bad conditions, and it can make copies of itself. The free-swimming jellyfish is just its way of spreading genes far and wide.The Big Transformation: Strobilation

Finally: The Medusa

Jellyfish Eggs and Blooms: What's the Connection?

Spotting and Identifying Jellyfish Eggs: A Practical Guide

What You See

Likely Culprit

Key Differences from Jellyfish Eggs/Larvae

Clear, gelatinous blobs with dots inside, often on seaweed or the beach.

Sea Gooseberries (Comb Jellies) or Salp chains.

Comb jellies are often bioluminescent and have a more defined shape. Salps are barrel-shaped and filter feeders. Neither are true jellyfish, and their eggs are handled differently.

Long, stringy, brownish or white snot-like strands.

Bryozoans (like "sea snot") or worm egg masses.

Bryozoans are colonial animals that feel gritty. They form fixed, lace-like structures, not free-floating clouds.

Small, individual spherical eggs in a cluster, often orange or red.

Snail or nudibranch egg masses.

These are usually laid in very organized, ribbon-like or spiral patterns on surfaces, not free-floating.

A diffuse, milky cloud in the water, especially at night.

Possible jellyfish planulae mass OR plankton bloom (like dinoflagellates).

Plankton blooms can be bioluminescent at night. Jellyfish planulae clouds are more localized and don't typically glow. This is the trickiest one to distinguish without a sample.

Tiny white specks swimming erratically in an aquarium.

Copepods or other beneficial microfauna.

These move in quick, darting motions. Newly hatched brine shrimp also do this. Jellyfish planulae have a more deliberate, slow, tumbling movement.

Jellyfish Eggs in Your Aquarium: Nuisance or Opportunity?

Answering Your Burning Questions About Jellyfish Eggs

Are jellyfish eggs in water dangerous to humans?

How long does it take for a jellyfish egg to become an adult?

Can you eat jellyfish eggs?

What eats jellyfish eggs and polyps?

The Bigger Picture: Why Should You Care?

Here's the thing most people get wrong: You rarely find a single, distinct "egg" like a chicken's. The beginning of a jellyfish's life is usually a microscopic, often free-floating stage that's easy to miss. Calling them "eggs" is a bit simplistic, but it's the term everyone searches for, so we'll roll with it while unpacking the much more complex reality.

A personal gripe: A lot of sensational news reports make jellyfish blooms seem like an alien invasion. Framing it that way misses the point. They're not attacking; they're just thriving in the environment we've accidentally engineered for them. They're a symptom, not the disease itself.

Comment