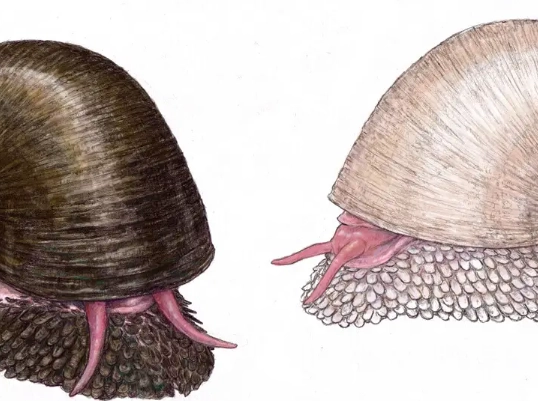

You've probably seen the pictures. A snail with a suit of armor, living in one of the most extreme places on Earth. The scaly foot gastropod, or Chrysomallon squamiferum if you want to get scientific, is a marvel. But when you strip away the "iron snail" hype and the deep-sea mystery, one of the first practical questions that pops up is a simple one: just how big is this thing? I remember digging through research papers early on, expecting some monstrous creature, and being genuinely surprised. The answer isn't as straightforward as you might think, and the scaly foot gastropod's size tells a fascinating story about survival under pressure. Quick Answer: Most adult scaly foot gastropods have a shell width (the broadest part) ranging from about 32 millimeters to 45.5 millimeters. That's roughly the size of a golf ball or a large walnut. Their shell height is typically a bit smaller. But those numbers alone don't capture the whole picture—not even close. Why does the scaly foot gastropod size matter so much? Well, in the deep sea, size is never just size. It's a direct result of energy availability, predator pressure, and the physical limits of the environment. A few millimeters can be the difference between thriving and just surviving. When we talk about the dimensions of this snail, we're really talking about its entire life strategy. Let's get specific. When scientists measure these snails, they don't just give one number. They look at shell width (the diameter) and shell height (from the tip of the spire to the bottom of the aperture). The scaly foot gastropod size is usually defined by its width, as it's a globose, almost spherical shell. The commonly cited range for a mature adult is that 32 mm to 45.5 mm in width. The largest specimen officially recorded? I've seen references to one with a shell width hitting about 46 mm. That's pretty much the upper limit. Now, compare that to a common garden snail, which can easily be 25-35 mm. It's not a giant. In fact, its compact, robust shape is a key feature. I have to admit, the first time I held a 3D-printed model scaled to 45 mm, I was struck by how dense it felt. It's not a lanky or elongated shell. It's a chunky, solid little dome. That shape makes perfect sense when you realize it's built to withstand the forces around a hydrothermal vent chimney. The shell height is generally less than the width. Think of a slightly squashed sphere. This low, wide profile gives it stability on the rocky, uneven surfaces of vent chimneys. A tall, spire-heavy shell would be more prone to toppling over in the turbulent currents. So, the scaly foot gastropod's size and shape are a perfect package deal. This is where it gets unique. The scaly foot gastropod's name comes from the hundreds of tiny, mineralized sclerites (scale-like plates) covering its fleshy foot. When discussing size, we often forget this "exoskeleton." These sclerites add to the animal's overall bulk and effective size from a predator's perspective. They create a spiky, armored skirt around the perimeter of the shell's opening. So, if you include the sclerites, the animal's effective "footprint" or living space it occupies is larger than the shell measurements suggest. It's like a knight in armor—the metal plates make the person inside seem bigger and more formidable. The sclerites might add several millimeters to the perceived width of the animal when it's extended and moving. It didn't just randomly evolve to be golf-ball sized. Every millimeter is optimized. Here’s the logic behind the scaly foot gastropod size. Energy Budgets are Tight: Hydrothermal vents are oases, but not all-you-can-eat buffets. The chemosynthetic bacteria living in the snail's enlarged esophageal gland (its food source) provide limited energy. Growing a massive shell and body requires more resources than the snail can reliably muster. The current size represents a sweet spot—large enough to support necessary organ systems (like a huge heart to circulate blood to its symbionts) but small enough to be sustained by its environment. Predator Defense: Its main predators are probably other vent inhabitants like crabs and possibly other snails. A larger shell would be heavier and more energetically costly to mineralize with iron sulfides. A smaller shell might be easier to crush. The 30-45 mm size, combined with its iron armor, likely presents a "Goldilocks" level of defense: tough enough to deter most attacks without being an impossible metabolic burden. Physical Constraints of the Habitat: They live on the sides of active hydrothermal vent chimneys. These are dynamic, often narrow structures with fierce temperature and chemical gradients. Being a compact, adherent animal allows it to hold on tight and navigate these micro-habitats. A much larger snail would struggle to find enough suitable real estate on a single chimney. Think of it as a deep-sea studio apartment. It's compact, efficient, and has everything it needs to survive in a very specific location. Upsizing isn't an advantage there; it's a liability. You can't just drop a ruler down 2,400 meters. Determining the scaly foot gastropod size is a meticulous process. Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) like Jason or Alvin collect specimens with extreme care. Once on the surface, the measurement is done with precision calipers, often under a microscope for accuracy. But it's more than just physical specimens. A lot of size data now comes from high-definition video and imagery from ROVs. Scientists can use laser scalers mounted on the ROV—two parallel laser points a known distance apart (usually 10 cm) projected onto the seafloor. By comparing the snail to these reference points in video frames, they can estimate the size of living snails in situ without ever touching them. This is crucial for understanding the population structure and growth in the wild. Here’s a breakdown of the key metrics they look for: Accurate measurement is the foundation for all other science. Is the population healthy? Are they growing normally? It all starts with knowing the scaly foot gastropod size. Good question. From the literature I've read, there's no significant sexual dimorphism in terms of shell size. You can't tell a male from a female just by looking at the shell dimensions. The differences are internal. This is common in many gastropods. So, that 45 mm champion could be either sex. The scaly foot gastropod doesn't hatch out looking like a miniature tank. Its size journey is a fascinating one. After a larval stage in the water column (how they disperse between vent fields), they settle onto the vent habitat as tiny juveniles. These juveniles have a shell, but it's thin and lacks the full mineralization of the adults. The iconic sclerites are also underdeveloped. Growth is relatively fast initially in the resource-rich vent environment, but it slows down as they approach maturity. Reaching that full scaly foot gastropod size of 35+ mm might take several years, though the exact growth rate is hard to pin down in the deep sea. The shift from a calcium carbonate-dominated shell to one fortified with iron sulfides (greigite and pyrite) is a gradual process as the snail matures and its symbiont population establishes. So, a snail's size is also a rough indicator of its age and life stage. Finding a population with a good mix of small, medium, and large individuals is a sign of a healthy, reproducing community. A site with only large adults might be an aging population without successful recent recruitment. The Size-Health Connection: In deep-sea conservation, size-frequency distribution is a critical monitoring tool. A shift towards smaller average sizes in a population could indicate environmental stress, over-collection, or a disruption in the vent fluid chemistry that supports their food source. Tracking scaly foot gastropod size over time is a non-invasive way to check the pulse of the entire vent ecosystem. To appreciate the scaly foot gastropod size, let's put it in context. It's not the biggest vent snail out there. For example, the vent-endemic snail Alviniconcha species can have shells exceeding 80 mm in height—much larger. But Alviniconcha has a different body plan and lifestyle, often living in warmer, more diffuse flow areas. The scaly foot gastropod is more comparable in size to other snails in its family (Peltospiridae), but it's the mineralization that sets it apart. Another famous vent snail, the "vent limpet" of the genus Lepetodrilus, is usually under 10 mm—much smaller. So, our iron snail sits comfortably in the mid-range for vent gastropods. Its claim to fame isn't sheer magnitude, but the incredible density and unique composition of its shell and sclerites at that specific size. Bigger isn't always better. In the deep sea, optimized is. Let's tackle some of the specific things people are searching for. These are the questions I had, and the ones I see popping up in forums and discussions. It seems incredibly rare. The environmental and energetic constraints we talked about appear to set a firm upper limit. While there might be an occasional outlier, the maximum scaly foot gastropod size is consistently reported around that 45-46 mm mark across different vent sites (like the Indian Ocean's Kairei and Longqi fields). Finding one bigger would be a notable discovery. Absolutely. The incorporation of iron sulfides (which are dense minerals) into the shell and sclerites significantly increases their weight compared to a similarly sized snail with a standard calcium carbonate shell. This weight is a trade-off. It makes them less buoyant and likely requires more energy to move, but it provides that unparalleled armor. It's the deep-sea equivalent of wearing a bulletproof vest—it adds pounds, but for good reason. A practical hurdle! It's Chrysomallon (Kris-oh-MAL-on) squamiferum (skwa-MI-fer-um). Now you can sound like a pro when you talk about its size. This is a great point. Their fame comes from their unique adaptations, not their stature. They're a perfect example of how evolutionary innovation often happens in small packages. They solved a massive problem (surviving in a hot, acidic, predator-filled environment) with a compact, brilliantly engineered solution. The scaly foot gastropod size is a feature of that efficiency. This isn't just academic. Understanding the typical and maximum scaly foot gastropod size has direct implications for its survival. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists Chrysomallon squamiferum as Endangered. One of the major threats is potential deep-sea mining. Mining operations targeting polymetallic sulfides around hydrothermal vents would completely destroy its habitat. Knowing their size and population density helps scientists argue for the protection of specific vent fields. If we know they need a certain amount of hard substrate on active chimneys to maintain a viable population of adults at their known size range, we can better define what areas need to be set aside as protected. For authoritative information on its conservation status, the IUCN Red List entry for Chrysomallon squamiferum is the definitive source. It details the threats based on the best available science, which includes data on their distribution and, by extension, the habitats that support their specific size and life history. Furthermore, institutions like the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History house type specimens and conduct ongoing research into deep-sea fauna, providing the foundational taxonomy and morphology studies that define how we measure and understand these animals. Writing this, it's hit me how fragile this balance is. A creature that builds itself with iron, one of the toughest materials around, is ironically so vulnerable to human activity. Its size, a masterpiece of deep-sea evolution, offers no protection against a collector's grab or a mining machine. That's a sobering thought. You won't find one in a home aquarium. The pressure, temperature, and chemical requirements are impossible to replicate. Your best bet is a major natural history museum with deep-sea exhibits. Some have excellent models or even preserved specimens. Seeing a life-sized model really drives home the scaly foot gastropod size—it's small enough to fit in the palm of your hand, yet complex enough to keep scientists busy for decades. So, the next time you see that amazing picture of the "iron snail," you'll know you're looking at a creature that's not a giant, but a titan of adaptation. Its size is a perfect, compact testament to life's ability to engineer solutions in the most unlikely places. Every millimeter tells a story of heat, pressure, chemistry, and survival. And that's a story worth knowing, no matter its size.Quick Guide

Breaking Down the Numbers: Shell Width, Height, and What They Mean

Beyond the Shell: The Sclerites and Foot

Why Is the Scaly Foot Gastropod This Specific Size?

Measuring Up: How Scientists Determine Scaly Foot Gastropod Size

Measurement

Typical Range (Adult)

Why It's Important

Measurement Method

Shell Width (Diameter)

32 - 45.5 mm

Primary indicator of overall size and maturity. Used in most population studies.

Digital calipers on collected specimens; laser scaling from ROV video.

Shell Height

~28 - 40 mm

Indicates shell shape and growth pattern. A lower ratio of height/width suggests a more robust, adapted form.

Digital calipers.

Aperture Width

~20 - 28 mm

Relates to the size of the foot and soft body that can be retracted. A wider aperture allows for a larger foot with more sclerites.

Calipers or microscopic image analysis.

Sclerite Length

Up to 8 mm

Shows the development of the unique dermal armor. Longer sclerites mean more extensive protection.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for detail.

Growth Stages: From Larva to Iron-Clad Adult

How Does Their Size Compare to Other Deep-Sea Snails?

Common Questions About Scaly Foot Gastropod Size

Can they get bigger than 45 mm?

Does the iron shell make them heavier for their size?

How do you even pronounce its scientific name?

Why are they so small if they're so famous?

The Bigger Picture: Size, Conservation, and Why It All Matters

What If You Want to See One?

"The integration of the iron sulfide-coated sclerites with the shell creates a continuous defensive barrier, making the animal's vulnerable tissues a challenging target regardless of attack angle. Its size is thus a combination of biomineralized structures."

Is there a difference in size between males and females?

Comment