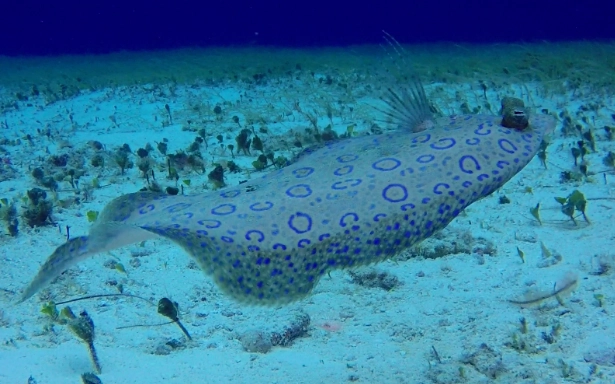

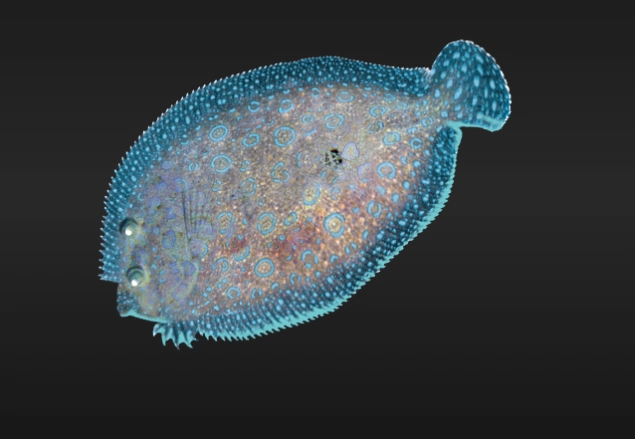

You're snorkeling over a sandy patch between coral heads. The scene looks empty, just beige rubble. You kick forward, and suddenly the "sand" erupts in a flurry of motion right beneath you. A flat, patterned fish you never saw darts away and vanishes again a few feet later. That heart-stopping moment? You've just met the peacock flounder (Bothus mancus). It's not magic, but it might as well be. This fish is the Houdini of the reef, a living lesson in optical illusion that makes even the best camouflage clothing look laughably obvious. Most articles will tell you it's flat and can change color. Big deal. After years of diving and keeping marine aquariums, I've seen what most guides miss. The real magic isn't just that it hides, but how it pulls off this trick in milliseconds, and the surprising ways this ability shapes its entire life—from hunting to avoiding becoming dinner itself. Let's get past the basic facts and into what makes this creature a true master of disguise. Calling it a "flatfish" is an understatement. As a larva, it looks like a normal, upright fish. Then, in one of nature's weirdest metamorphoses, one eye migrates over the top of its head to join the other on the same side. The fish then tips over and lives its life sideways, with both eyes on the upward-facing side. The peacock flounder's upper side is the left side (it's a "left-eyed" flounder). This gives it a panoramic, upward view perfect for spotting prey and predators while its body is flush against the seabed. Quick ID Card: The "peacock" name comes from the stunning blue rings and spots, often edged in black, that decorate its upper side. Males tend to have longer, more spaced-out fins between their eyes. They're not huge—maxing out around 18 inches (45 cm)—but in the shallow reef world, that's a respectable size. Here’s how it stacks up against some other common flounders you might hear about: This is where it gets incredible. It's not just one trick; it's a multi-layered system. Under its skin are specialized cells called chromatophores containing pigments. By expanding or contracting these cells, the fish can change its color and pattern. Think of them as biological pixels. Research cited by the Florida Museum of Natural History suggests flounders have some of the most complex chromatophore systems among fish. But here's the kicker—it's not just reacting to color. It's matching pattern. The biggest mistake people make is thinking this is a reflexive, skin-based trick. It's brain-based. The flounder must see the substrate below it to match it. If you put one on a checkerboard pattern it can see, it will try to create squares. If its eyes are covered, it can't change appropriately. Its eyes, perched on stalks, can move independently to get a good look at the seafloor. It goes beyond flat color. The peacock flounder can adjust the contrast of its spots to mimic the graininess of sand or the speckles of coral rubble. It can also alter the shade of its skin to account for light filtering through water, matching not just the color but the apparent brightness of its surroundings. Sometimes, it will partially bury itself in sand, leaving only its eyes and the top of its head exposed, completing the illusion. You'll find Bothus mancus across the Indo-Pacific, from the Red Sea and East Africa all the way to Hawaii and the Pitcairn Islands. It's a creature of shallow, sun-drenched waters, usually from 3 to 150 feet deep. Its world is a mosaic: Its behavior is a study in patience and explosive action. It lies in wait, often with just a gentle undulation of its fringed edges to settle sand over itself. Small fish, crabs, and shrimp that wander too close are doomed. The strike is a sudden, upward lunge, creating a brief puff of sand. After a successful hunt, it often settles back into a slightly different spot, recalibrating its camouflage all over again. Okay, you want to find one. It's a rewarding challenge. Forget just swimming around looking for a fish. You're looking for anomalies. 1. Look for the Eyes. This is the golden rule. Scan sandy bottoms slowly. Look for two tiny, golf-ball-like protrusions close together. They might move independently. Once you spot a pair of eyes that don't belong to a crab or a goby, you've found your flounder. 2. Watch for the "Halo" Effect. A perfectly camouflaged flounder can still cast a very faint, thin shadow on the sand. On a sunny day in clear water, look for an oval-shaped shadow that seems disconnected from any obvious object. 3. The Flush Technique. Swim slowly and steadily about a foot or two above the bottom. Your approach from above is less likely to trigger a flight response than a direct frontal approach. Sometimes, the movement of your shadow or a subtle vibration will cause it to flinch just enough for you to see the outline. 4. Prime Locations. In Hawaii, places like Hanauma Bay's sandy channels are famous for them. In the Caribbean, while not the same species, similar flounders can be found using these techniques. Check data from citizen science projects like Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) surveys for popular sighting spots. The thrill isn't in seeing a colorful fish out in the open. It's in that moment of perception, where your brain finally resolves the puzzle on the seafloor. Nothing beats it. Let's be brutally honest. This is an expert-only animal, and many sources sugarcoat the challenges. Yes, they are occasionally sold. The temptation is huge—a living piece of art that changes daily. But here’s what they don't tell you at the fish store: If you're still determined, the setup is everything: fine, sugar-sized sand, subdued lighting, plenty of flat hiding spaces, and immaculate water quality. It's a commitment to keeping a fascinating predator, not a community reef centerpiece. So next time you're floating over what looks like empty sand, look closer. That might not be the seafloor. It might be one of the ocean's greatest illusionists, the peacock flounder, watching you, perfectly hidden in plain sight. The real wonder isn't just finding it, but understanding the breathtaking biological machinery that makes its disappearance possible.

What's Inside This Guide

More Than Just a Pancake: Peacock Flounder Biology 101

Feature

Peacock Flounder (Bothus mancus)

Summer Flounder (Fluke)

European Plaice

Primary Habitat

Tropical coral reefs & sandy patches

Temperate Atlantic coastal sands

Cold North Atlantic seabed

Key Identifying Mark

Vivid blue rings & spots

Eye-like spots with pale halos

Orange or red spots

Camouflage Speed

Extremely fast (seconds)

Moderate

Slower

Notable Quirk

Can see ahead while buried in sand

Aggressive, predatory strikes

Mouth is small, adapted for worms

How Does the Peacock Flounder Achieve Its Camouflage?

The Chromatophore Network: Living Pixels

Visual Input: It Needs to See to Disappear

The Finer Details: Texture and 3D Illusion

Life on the Bottom: Habitat and Secret Behaviors

How to Actually Spot One in the Wild (Pro Tips)

The Peacock Flounder in a Home Aquarium: A Reality Check

Your Questions Answered by a Marine Life Enthusiast

What's the biggest mistake divers make when trying to photograph a peacock flounder?

Coming in head-on and from a low angle. This triggers their flight instinct immediately. You'll just get blurry shots of sand. Approach from directly above, very slowly. Get your camera settings ready before you descend. Use a slight downward angle. The goal is to capture it relaxed, with its camouflage fully engaged, not in mid-escape.

Can a peacock flounder match a brightly colored coral, or just sand and rubble?

They are better at matching granular, mottled patterns like sand, rubble, or mixed substrates. While they can adjust their base color, replicating the intense solid colors of a healthy coral head (like bright red or purple) is beyond their capability. You'll most often find them on or near substrates they can convincingly mimic.

I'm setting up a large predator tank. Is the peacock flounder's camouflage affected by artificial aquarium lighting?

It can be. If your lights are too stark, bright, or a different color temperature than natural sunlight, it can throw off their matching ability. They might appear constantly dark or mottled, never quite settling. Using LED lights with adjustable spectrums and ramping them up/down to simulate a natural day cycle helps. Avoid actinic-heavy "blue" lighting as the primary source; it doesn't illuminate the tank bottom in a way they can interpret accurately for camouflage.

How do they avoid being eaten by larger predators like rays or sharks?

Their first and best defense is, of course, not being seen. If that fails and a predator disturbs the sand near them, they erupt in a short, incredibly fast burst of speed—usually in an unpredictable zig-zag—and then slam back onto the bottom a few feet away, immediately starting the camouflage process again. This "flush and re-settle" tactic breaks the predator's visual lock. Their flat profile also makes them difficult to grab and swallow for many fish.

Comment