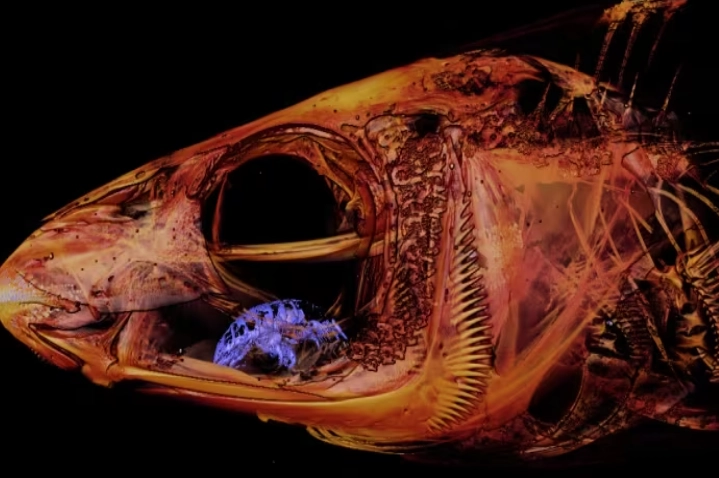

You reel in a nice-looking snapper. You go to clean it, pry open its mouth, and instead of a tongue, you see a pale, bug-like creature staring back at you. It's not a nightmare. It's Cymothoa exigua, the tongue-eating louse. This crustacean doesn't just hitch a ride; it performs a functional organ replacement that would make a sci-fi writer jealous. The fish lives on, using the parasite as a prosthetic tongue. It's one of the most bizarre and specific parasitic relationships in the ocean. I've been studying marine parasites for over a decade, and this one still makes me shake my head in a mix of horror and admiration every time I see it. Most articles just call it "weird" and move on. But if you're an angler, a fish farmer, or just a curious soul, you need to know more than that. You need to know how it happens, which of your favorite fish are targets, and what it really means for the ecosystem—and your dinner plate. First, let's clear up a common mistake. Calling it a "louse" is a bit misleading. It's not an insect. Cymothoa exigua is an isopod, a type of crustacean, making it a distant cousin of shrimp, crabs, and pill bugs. The term "tongue-eating louse" stuck because it's graphic and memorable, but "parasitic isopod" is more scientifically accurate. These creatures are sex-changers. They all start life as males. When a juvenile male finds a suitable host fish, it enters through the gills and makes its way to the mouth. If it's the first to arrive and successfully attaches, it will transform into a much larger female. She can grow up to 3 cm long. Any later arrivals remain as smaller males, living in the gill chamber and mating with the female. It's a tiny, self-contained harem inside a fish's head. Quick Specs: The female Cymothoa exigua is the star of the show. She's the one that latches onto the tongue stump. Her body is segmented, creamy-white to light brown, and she uses her front claws (pereopods) to anchor herself firmly. She feeds on blood from the tongue's arteries or on mucus, not on the fish's food. That's a crucial detail many get wrong. The process isn't a single bite. It's a slow, methodical takeover. Let's break down this real-life horror movie scene step-by-step. The tiny, free-swimming male isopod finds a host. It doesn't randomly bite. It specifically enters through the gill arches, a common entry point for many fish parasites. From there, it navigates to the buccal cavity—the mouth. Once in the mouth, it attaches to the base of the tongue using its claws. If it's the dominant parasite in the location, hormonal triggers initiate its change to female. This transformation takes time, during which it starts its feeding. Here's the subtle error most descriptions make. The isopod doesn't typically chew the tongue off in a frenzy. It attaches to the tongue and feeds on the blood supply. This constant drain of nutrients and physical damage causes the tongue tissue to atrophy—to waste away and eventually fall off. It's a process of starvation and necrosis, not consumption. The parasite severs the blood vessels, and the tongue simply degenerates. Once the original tongue is gone, the female isopod positions her own body into the exact spot. Her rear end aligns with where the tongue root was. The fish's muscles actually adapt and grasp onto the parasite. Studies, like those referenced in the Journal of Parasitology, suggest the fish can use the isopod to help manipulate food. The parasite becomes a functional, living prosthetic. The fish doesn't die from this. It can live for years with its new "tongue." The parasite gets a steady food source (blood/mucus) and protection. From an ecological perspective, it's a brutally efficient adaptation. This isn't a global plague. Cymothoa exigua has a known range, primarily in the Eastern Pacific, from the Gulf of California down to coastal waters of Ecuador and Chile. It's also been recorded in the Atlantic. It's host-specific but not to a single species. It prefers certain families of fish. If you're fishing in these areas, here are the fish you're most likely to find hosting this peculiar tenant: You won't find it on open ocean pelagic fish like tuna or marlin. It's a coastal, inshore parasite. The isopod's lifecycle depends on the fish's behavior and habitat overlapping with where the juvenile parasites are swimming. A Note for Aquarists: This is a big one. There are documented cases, though rare, of similar tongue-eating isopods (different Cymothoa species) showing up in home aquariums via live feeder fish or newly acquired wild-caught specimens. Always quarantine new arrivals, especially wild-caught fish. The horror of finding one in a closed-system tank is real. This is the question everyone asks with a slight shudder. Let's be unequivocally clear. No, Cymothoa exigua cannot infect humans. It is not a human parasite. Its biology, lifecycle, and attachment mechanisms are exquisitely adapted to specific fish hosts. It cannot survive in the human body, attach to a human tongue, or cause us any direct parasitic harm. The only potential risk is indirect and relates to food safety, as with any parasite in fish meat. From a conservation and fishery management perspective, high infestation rates in a local population could be a sign of environmental stress or high parasite loads, which is worth monitoring. Resources like FishBase often catalogue host-parasite relationships, helping scientists track these dynamics.

What's Inside This Deep Dive?

What Exactly is the Tongue-Eating Parasite?

How Does the Parasite Execute Its Tongue Replacement?

Step 1: The Infiltration

Step 2: The Attachment and Transformation

Step 3: The "Eating" (It's More Like Starving)

Step 4: The Replacement

Which Fish Are Most at Risk from Cymothoa exigua?

Can the Tongue-Eating Parasite Affect Humans?

Your Burning Questions Answered (FAQs)

I caught a fish with the parasite still in its mouth. Is the meat of that fish safe to eat after I remove the bug?

In almost all cases, yes. The parasite is localized to the mouth. It does not migrate through the muscle tissue we eat. The standard rule is to remove the parasite, cut out a bit of the surrounding tissue in the mouth where it was attached as a precaution, and then fillet the fish as you normally would. As always, cook the fillets thoroughly. The main contamination risk is from bacteria, not from the parasite spreading through the body.

Are there other parasites that do similar "body part replacement" tricks?

Cymothoa exigua is the champion of tongue replacement, but it's not alone in bizarre parasitism. Some parasitic barnacles (like Sacculina) castrate crabs and manipulate their behavior, essentially turning them into zombie nurseries. Certain trematode parasites cause snails to grow swollen, pulsating tentacles that look like caterpillars to attract birds. Nature is full of parasites that modify their hosts in extreme ways, but full functional organ replacement like the tongue-eater is exceptionally rare.

As a recreational angler in California, how common is this, and should I be checking every fish I catch?

It's not super common, but it's not a once-in-a-lifetime find either, especially if you're targeting snappers or croakers in its known range. You don't need to panic-check every fish. However, it's good practice to quickly inspect the mouth and gills when you're cleaning your catch, not just for Cymothoa but for any other parasites or abnormalities. If you do find one, report it to local marine science institutions or fish and wildlife agencies if they have a reporting system. Citizen science data can be valuable.

Can the fish survive and thrive long-term with the parasite as a tongue?

They can survive, but "thrive" is debatable. Research indicates infected fish often have lower body weight compared to uninfected ones of the same size. The parasite is a drain on the host's resources. While the fish can still eat, the efficiency of its feeding might be compromised. It's a compromised life, not a symbiotic partnership where both benefit equally. The fish tolerates it because the alternative—trying to dislodge it—is likely impossible or more damaging.

Has this parasite inspired any pop culture?

Absolutely. Its sheer grotesque brilliance has made it a favorite in horror and sci-fi. The most direct reference is the 2012 creature feature movie The Bay, where a mutated version of Cymothoa becomes a threat to humans (taking massive artistic license, of course). It frequently appears in "world's weirdest parasites" lists and documentaries. It's a perfect example of reality being stranger than fiction.

Comment