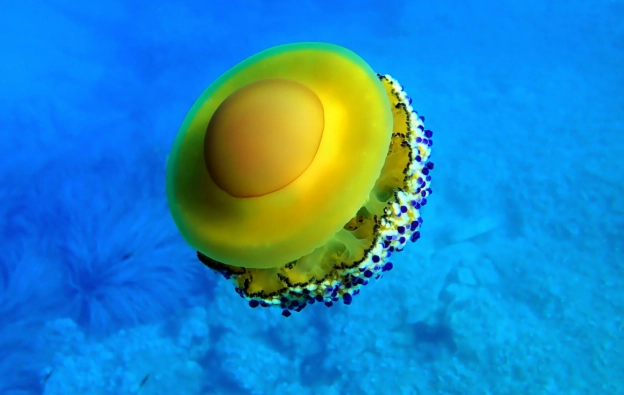

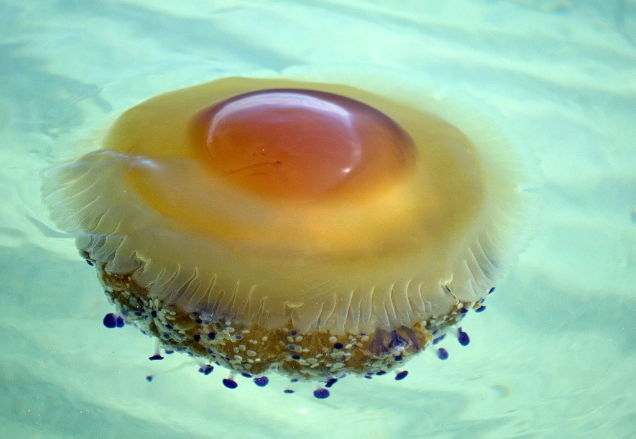

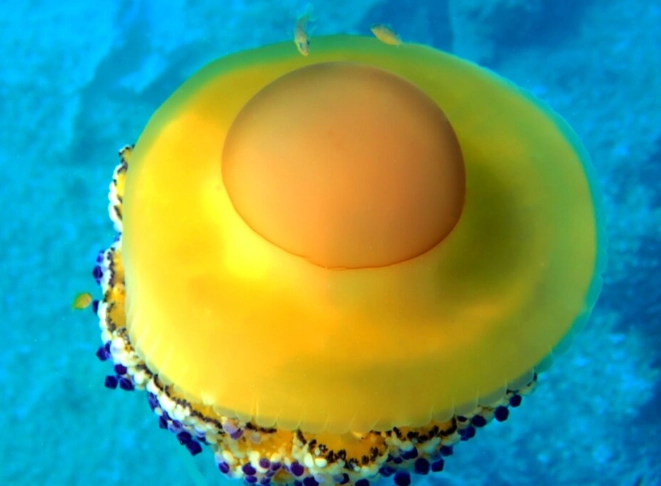

If you've ever spent time by the ocean, you've probably seen jellyfish. But have you ever wondered where they come from? That's where the fascinating, often overlooked world of egg jellyfish comes in. It's not one single species. "Egg jellyfish" refers to the critical early stages in a jellyfish's life cycle—the eggs, larvae, and sometimes the polyps—before they become the pulsating bells we recognize. Understanding this phase is key to everything from predicting blooms to appreciating the ocean's delicate balance. I remember the first time I saw what I thought was a weird, melting plastic bag in a tide pool. It was a translucent, frilly mass. Turns out, it was the egg-laden oral arms of a moon jellyfish. Most beachgoers walk right by these hidden nurseries. Let's clear this up first. You won't find a species officially named "egg jellyfish." The term is a catch-all for the reproductive and immature forms of jellyfish. This includes: When people talk about seeing "egg jellyfish," they're usually referring to visible egg masses carried by adult females. The moon jellyfish (Aurelia aurita) is the classic example. Females carry fertilized eggs in specialized pouches on their oral arms, which look like a faint, smoky, or granular haze within the jelly's clear bell and frilly arms. Most online guides miss this: that clear, firm, rubbery blob you find on the beach? It's probably not a jellyfish egg mass. It's more likely a colony of tunicates (sea squirts) or salps. True jellyfish egg matter is incredibly fragile and rarely washes ashore intact. It usually disintegrates quickly. This misidentification is a huge gap in common knowledge. This table breaks down the common look-alikes. Getting this right is the first step to being a savvy observer. The big takeaway? If it's on the beach and intact, it's probably not jellyfish eggs. The real egg action happens on the living animal or hidden away as microscopic polyps. Jellyfish have a complex life cycle called "alternation of generations." It involves both sexual (medusa) and asexual (polyp) phases. Most people only know half the story. Adult jellyfish (medusae) are the sexual stage. Males release sperm into the water. Females, like the moon jelly, often catch this sperm to fertilize eggs they're carrying. Others release eggs into the plankton. This is where the "egg jellyfish" journey begins—as a fertilized egg. This is the part most nature documentaries skip. The fertilized egg develops into a planula larva. This tiny, hairy speck swims for a few days before attaching to a hard surface—a rock, a dock piling, a shell. It then transforms into a polyp. Here's the kicker: the polyp is immortal, in a sense. It can live for years. It feeds. And most importantly, it clones itself. Through a process called strobilation, a single polyp can produce a stack of tiny juvenile jellyfish called ephyrae, releasing them one after another. One polyp colony can be the factory for thousands of adult jellyfish. This is why jellyfish blooms can seem to appear out of nowhere. The polyps have been there all along, waiting for the right water temperature and food conditions to start production. Research from institutions like the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) shows how sensitive this polyp stage is to environmental changes. You need to know where to look and when to look. It's not random. For Egg Masses on Adults: Your best bet is calm, sheltered waters like bays, marinas, and estuaries in late spring through summer. This is peak reproduction time for many species like moon jellies. Look for larger, often slightly milky-looking jellies. Use a snorkel or look off a calm dock. Public aquariums with jellyfish displays are a guaranteed way to see this stage clearly. For Polyps: This is the expert level. You're looking for the underside of things. Check the shaded sides of dock floats, the underside of large, stable rocks in the low intertidal zone, and on oyster or mussel shells. You'll need a magnifying glass or macro camera lens. They look like a field of tiny, white-ish flower buds. I've had the best luck on old, established marina structures in early spring, before algal growth covers everything. Egg and polyp stages aren't just transitional; they're ecological linchpins. They are a massive food source. Fish larvae, small crustaceans, and filter feeders feast on planulae and tiny ephyrae. This energy transfer is crucial. They are also a population control point. Most planulae and polyps don't survive. Predation, disease, and unfavorable conditions (like low oxygen) wipe them out. This natural bottleneck regulates how many adults form. Human activities like coastal construction (creating perfect polyp habitat) and warming waters (speeding up polyp metabolism and strobilation) can remove this bottleneck, leading to more frequent and severe blooms. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) studies these links closely, as jellyfish blooms can impact fisheries and coastal economies. Curiosity shouldn't lead to a sting. Even egg masses can retain stinging cells (nematocysts). Respect the process. You're peeking into a nursery. So next time you're by the sea, look closer. That faint haze in a jellyfish's bell isn't a flaw. It's the next generation. And those hidden polyps on the dock? They're the architects of future blooms. Understanding egg jellyfish means understanding the ocean's rhythms on a much deeper, more fascinating level.

What's Inside This Guide

What Exactly Are "Egg Jellyfish"?

A Common Misidentification

How to Spot the Difference: Egg Mass vs. Imposter

What You See

Likely Identity

Key Identifying Features

Texture & Consistency

Frilly, smoky haze inside a jellyfish's bell/arms

Moon Jellyfish Egg Mass

Still part of a living jellyfish. Appears as a granular, beige or brownish cloud.

Fragile, disintegrates if touched.

Clear, firm, gelatinous blob or sausage-shaped mass

Sea Squirt (Tunicate) Colony

Often has a more defined shape. May have visible, smaller individual organisms within.

Rubbery, springy. Holds its form.

Long, clear or slightly opaque chain or string

Salp Chain

Looks like a necklace of connected, barrel-shaped units. Each unit is an individual salp.

Gelatinous but more structured.

Small, white, rice-like grains on seaweed or shells

Jellyfish Polyps (possibly)

Requires a magnifying glass. Looks like tiny anemones or hydra.

Firm, attached.

The Full Lifecycle: From Egg to Adult

The Medusa's Role: Sex and Plankton

The Hidden Phase: The Polyp Empire

Where and When to Find Them

Why They Matter: The Ecosystem Role

Safety Tips for Observers

Your Questions Answered

How can I safely observe egg jellyfish in the wild?

The safest method is visual observation from a slight distance. Wear water shoes if wading. Never handle any jellyfish or gelatinous mass with bare hands, as even fragments of stinging cells (nematocysts) can cause irritation. Use a clear container or a net with a long handle for a closer look, and always return the specimen to the water quickly to minimize stress.

What's the main difference between a jellyfish egg mass and a salp or sea squirt colony?

Structure and texture are key. True jellyfish egg masses (like those of moon jellies) are often a loose cluster of individual eggs or planulae held in oral arms, resembling a faint, granular haze. Salps and sea squirts form more defined, geometric chains or firm, rubbery blobs. A quick test: gently prod with a stick. Jellyfish matter is fragile and breaks apart easily; tunicate blobs are tougher and spring back.

Why are egg jellyfish stages important for the overall marine ecosystem?

They are a critical bottleneck and a food source. The planula and polyp stages are vulnerable, and their survival rates directly impact future jellyfish blooms. Conversely, these stages are a primary food source for small fish, crustaceans, and even some sea turtles. They transfer energy through the food web. An imbalance here can ripple out, affecting fish populations and water clarity.

Can keeping jellyfish in an aquarium help me see their egg stage?

It's possible but notoriously difficult and not for beginners. Moon jellies (Aurelia) are the most common captive species that might reproduce. Success requires a perfectly stable, specialized kreisel tank, impeccable water quality, and a ready culture of microscopic food for the planulae. Most home aquarium attempts fail at the polyp stage due to unnoticed water parameter shifts. It's a fascinating project, but expect a high chance of failure without dedicated, expert-level systems.

Comment