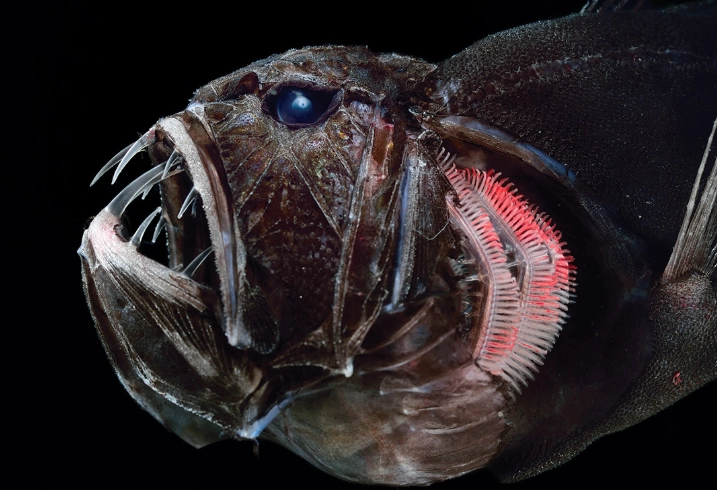

You see it in every monster movie. A dark shape in the water. A gaping maw. Rows upon rows of jagged, knife-like teeth. The imagery is so ingrained that we instinctively associate big fish teeth with pure, unthinking menace. But spend any real time observing aquatic life, and that Hollywood image starts to crack. I remember the first time I saw a barracuda up close while diving. Its mouth was slightly open, revealing those infamous fangs. My heart skipped a beat. But the fish just hung there, watching me with a curious eye, more interested in the smaller fish darting around than the clumsy bubble-blowing mammal in its space. Its teeth weren't a threat to me; they were simply the tools of its trade. The truth about big fish teeth is far more fascinating than the fiction. They aren't just weapons; they are highly specialized instruments shaped by millions of years of evolution to solve very specific dietary problems. From the serrated blades of a shark to the crushing molars of a sheepshead, each dental design tells a story about survival, niche, and ecological strategy. Let's get this straight from the start. A fish's mouth is a food processor, not a sword. Every aspect of its dental anatomy – size, shape, arrangement, number – is tuned to what it eats and how it gets that food into its stomach. Think of it like kitchen tools. You wouldn't use a butter knife to carve a turkey, and you wouldn't use a meat cleaver to fillet a delicate piece of sole. Fish have evolved their own specialized cutlery drawer. The great white shark's iconic triangular, serrated teeth are perfect for its job: grabbing and sawing through the tough, blubbery hide of seals and large fish. The serrations act like the teeth on a steak knife, reducing the effort needed to cut through connective tissue. On the other hand, a pike's needle-like teeth are angled backward. Their function isn't to slice, but to grip. Once a prey fish is in that mouth, those backward-facing needles make escape nearly impossible, allowing the pike to swallow its meal headfirst. Key Insight: The most "dangerous" looking teeth are often found on mid-sized hunters, not the absolute largest creatures in the sea. The real giants, like whale sharks and basking sharks, are filter feeders with thousands of tiny, vestigial teeth they don't even use for feeding. We can broadly categorize big fish teeth into a few functional archetypes. It's less about the fish's total length and more about the dental hardware. This is the group that fuels nightmares. Teeth are typically flat, triangular, and razor-edged. Sharks (Great White, Tiger, Bull): The masters of this domain. Multiple rows of teeth act as a conveyor belt; front teeth do the cutting, and when one is lost, a new one from the row behind slides forward. A single shark can go through tens of thousands of teeth in its lifetime. The shape varies: broad and serrated for cutting (great white), pointed and curved for gripping and tearing (tiger shark). Barracuda: Their fangs are long, dagger-like, and uneven. They're built for speed. A barracuda will accelerate and ram its prey, those teeth acting like spears to impale fish like mackerel or herring. The bite is designed to stun and hold, not to chew. These teeth look less intimidating but are incredibly powerful. They're dealing with armored prey. Sheepshead Fish: This one always gets a double-take. It has a set of chisel-like incisors in the front and flat molars in the back, eerily similar to human teeth. They use them to pry barnacles off pilings, crush crabs, and crack open mussels. I've watched them methodically work a dock piling, and the sound of their teeth scraping on shell is unmistakable. Triggerfish: Their teeth are fused into a powerful beak, like a parrot. This beak can exert tremendous force, allowing them to crunch through sea urchins, crabs, and coral. They're one of the few fish that can systematically de-spine a sea urchin to get to the good parts inside. Teeth are numerous, small, and often velcro-like. Their job is to create a seal or prevent escape. Piranhas: The myth is they can skeletonize a cow in minutes. The reality is their teeth are perfectly designed for their niche: scavenging and eating smaller fish. Their triangular, interlocking teeth are like a pair of sharp scissors. They bite down with incredible force for their size, shearing out a small chunk of flesh. The bite is a punch, not a sawing motion. Muskellunge (Muskie): Known as the "fish of ten thousand casts," this freshwater predator has hundreds of small, sharp teeth lining its jaws, tongue, and roof of its mouth. Once it clamps down on a large baitfish, there's no slipping free. For slicing blubber/muscle: Broad, flat, serrated teeth (Great White Shark). For crushing shells: Rounded molars or fused beak (Sheepshead, Triggerfish). For gripping slippery fish: Numerous small, needle-like teeth (Pike, Walleye). For shearing/scissoring flesh: Interlocking triangular teeth (Piranha). Here's where an expert perspective cuts through the common chatter. Misconception 1: Bigger fish always have bigger, scarier teeth. As mentioned, the biggest fish have no use for them. The whale shark's tiny teeth are a biological footnote. The real dental power is in the mid-sized specialist hunters. Misconception 2: Sharp teeth automatically mean "man-eater." Most fish with impressive dentition have zero interest in humans. We're not on their menu. A barracuda's teeth are for fish. A moray eel's teeth are for fish and octopus. They might bite in defense or if provoked (or if you're spearfishing and have struggling fish on you), but predation on humans is exceptionally rare. The risk is almost always a case of mistaken identity or defensive reaction. Misconception 3: The more teeth, the more dangerous. It's about tooth design and jaw muscle mechanics, not raw numbers. A piranha has fewer teeth than a pacu (its vegetarian cousin), but its bite force relative to its body mass is one of the strongest among vertebrates. A sheepshead fish has a very manageable number of teeth, but its jaw structure generates enough force to crack a crab shell with ease. Some dental strategies are just plain weird and wonderful. The Deep-Sea Fangtooth: It holds the record for the largest tooth-to-body-size ratio of any fish. Its teeth are so long it has special sockets in the top of its head to close its mouth. In the pitch-black depths, it's a "lunge and hope" predator. Those massive teeth ensure that anything it bumps into and bites isn't getting away. The Cookiecutter Shark: This small shark doesn't have rows of teeth for slicing. It has a unique set: small, pointed upper teeth to latch on, and a circular saw of large, triangular lower teeth. It attaches itself to a much larger animal (tuna, dolphins, even whales), twists its body, and uses those lower teeth to carve out a perfect plug of flesh, leaving a crater-like wound. It's a parasitic feeder, and its teeth are the specialized can opener. Teeth in the Throat: Many fish, including carp and some cichlids, have pharyngeal teeth – sets of teeth in their throat, behind the gills. These further process food after it's been swallowed, grinding plant matter or crushing shells. You never see them unless you dissect the fish, but they're a crucial part of the digestive toolkit. Understanding these adaptations changes how you see aquatic life. That "terrifying" mouth becomes a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering, a direct window into the fish's world, its diet, and its role in the ecosystem. It's biology, not horror.

What's in the Jaws?

Not Weapons, But Tools: The Functional Truth

Types of Teeth, Types of Menus

The Slashers and Slicers

The Crushers and Grinders

The Graspers and Holders

Dental Design at a Glance

The Biggest Misconceptions About Large Fish Teeth

Beyond the Obvious: Fascinating Dental Adaptations

Your Questions Answered

Why do some big fish have teeth that look so frightening?

It's not about being scary; it's pure function. For predators like the great white shark, large, serrated teeth are designed to saw through blubber and muscle. For piranhas, the triangular, interlocking teeth act like shears for slicing flesh. The shape and size directly correlate to their diet and hunting method. A fish's teeth tell you exactly what's on its menu.

Do all big fish have sharp, dangerous teeth?

Absolutely not. This is a huge misconception. Many of the largest fish in the ocean are gentle giants. Whale sharks and basking sharks, the two biggest fish species, are filter feeders with thousands of tiny, useless teeth. They swim with their mouths open, sifting plankton. The real dental powerhouses are often medium-sized hunters or specialized feeders.

What's the most common mistake when identifying a fish by its teeth?

Assuming all sharp teeth mean 'dangerous predator.' Take the sheepshead fish. It has impressive, human-like incisors and molars perfect for crunching crabs and barnacles. They look intimidating but pose zero threat to humans. Conversely, the pacu, a relative of the piranha, has blunt, human-like teeth for crushing nuts and seeds. Judging a fish solely by its dental appearance is a sure way to misread its ecological role.

How do fish replace lost or broken teeth?

Many fish have a conveyor belt system that puts sharks to shame. While sharks have rows of replacement teeth, some fish like the piranha have a single set of interlocking teeth that grow continuously, like rodent teeth, and are worn down by use. Others, like triggerfish, have teeth fused into a beak-like structure that constantly grows. The replacement mechanism is highly specialized to their specific feeding habits and the wear and tear their teeth endure.

Comment