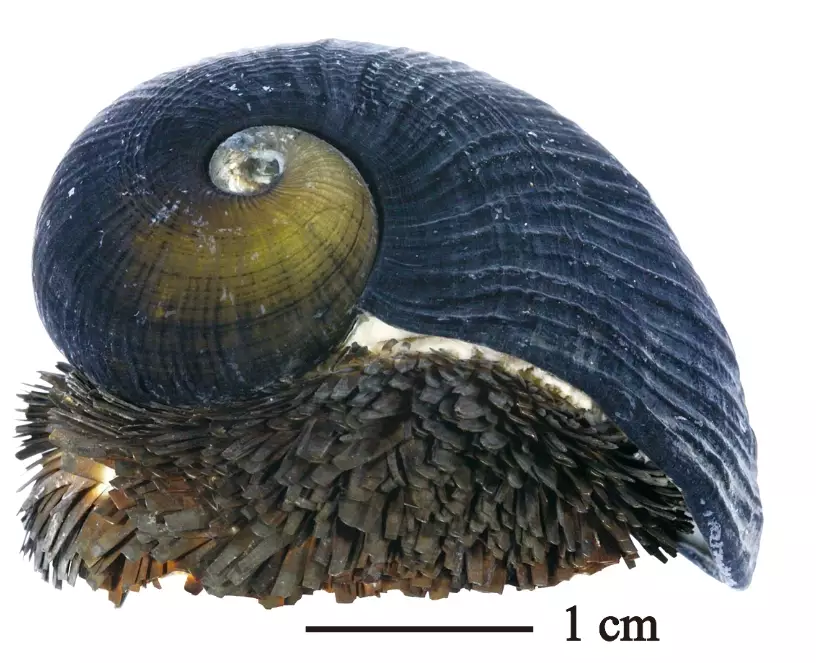

Picture this: a pitch-black landscape, 2,800 meters below the Indian Ocean's surface. The water is just above freezing. Then, through the gloom, you see chimneys billowing superheated, toxic fluid—a deep-sea hydrothermal vent. And crawling on these chimneys, looking like a tiny medieval knight forged in a demon's workshop, is the scaly-foot gastropod. Its name doesn't do it justice. This isn't just a snail. It's the only known animal on Earth to incorporate iron sulfide into its skeleton, building a living suit of armor. Forget everything you know about garden snails. This creature redefines survival. Let's get the basics out of the way. The scaly-foot gastropod (Crysomallon squamiferum) is a deep-sea snail discovered in 2001 on the Kairei hydrothermal vent field. Calling it a "snail" feels almost insulting. Yes, it has a soft body and a coiled shell. But that's where the similarity ends. Its most famous feature is the sclerites—hundreds of scale-like structures covering its fleshy foot. These aren't made of chitin or calcium carbonate like most animal armor. They're layered with greigite and pyrite. In plain English: iron sulfide minerals. The same stuff as fool's gold. Its outer shell layer is also fortified with these minerals. This is biomineralization on a whole other level. Scientific Name: Crysomallon squamiferum It doesn't have a mouth or a digestive system in the traditional sense. Instead, it relies on symbiotic bacteria housed in a special organ called the trophosome. These bacteria chemosynthesize, using the hydrogen sulfide from the vent fluids as an energy source to produce organic compounds, essentially cooking food from toxic chemicals. This is the million-dollar question. The prevailing theory is that it's a form of controlled waste management and defense, rolled into one. Here’s the step-by-step process as we understand it: Step 1: The Toxic Buffet. The snail lives in water rich in hydrogen sulfide (H₂S) and dissolved iron (Fe²⁺), which is toxic and abundant from the vent fluids. Step 2: Bacterial Detox. Its gills absorb H₂S and transport it to the symbiotic bacteria in the trophosome. The bacteria use it for chemosynthesis. This process likely creates sulfur byproducts. Step 3: Mineral Assembly Line. The current thinking is that the snail actively transports iron from the environment into specialized cells at the base of its sclerites and the outer shell layer. There, it combines with sulfur (possibly from the bacterial symbionts or the environment) to form iron sulfide nanoparticles. Step 4: Layered Defense. These nanoparticles are assembled into the complex, layered structure of the sclerites. The inner core is organic, the middle layer is where the dense iron sulfides sit, and the outer layer is a thin organic coat. This creates a composite material—tough but not too brittle. Many articles state the snail "extracts iron from the water." That's overly simplistic and a bit misleading. The exact biochemical pathway is still under investigation. A key debate is about the source of the sulfur. Is it purely from the environment? Or do the sulfur byproducts from its internal bacterial symbionts get shuttled to the mineralization site? This latter possibility would be incredible—a direct link between its energy production and armor construction. Some researchers I've spoken to lean towards an environmental source, but the symbiont pathway hasn't been ruled out. This nuance matters because it changes how we view the integration of its biology. You can't talk about the scaly-foot gastropod without describing its home, because they are inseparable. It's found only on active hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean. We're talking about two main neighborhoods: Think of these vents as deep-sea geysers. They spew superheated water (up to 400°C/750°F) loaded with minerals and chemicals. The scaly-foot gastropod doesn't live in the blistering plume. It lives on the chimney walls where warm, chemical-rich water seeps out—a gradient zone where 2°C water meets 400°C fury. One wrong move and it's boiled or frozen. The real estate is also temporary. Vents are ephemeral, active for decades maybe, before shutting off. When the vent dies, the entire ecosystem collapses. The snail's larvae must find a new, active vent across miles of barren seafloor. It's a lottery with astronomical odds. Focusing solely on the iron armor is a mistake. The scaly-foot gastropod is a masterclass in integrated adaptation. The armor is just one tool in the box. The Symbiotic Engine: This is its core survival mechanism. The bacteria in its trophosome allow it to thrive independent of sunlight or organic food falling from above. It lives off the Earth's geothermal energy. Pressure Resistance: Its proteins and cell membranes are adapted to function normally under 250+ atmospheres of pressure. Bring it to the surface, and it disintegrates. Toxin Tolerance: Its tissues can handle levels of hydrogen sulfide and heavy metals that would instantly kill almost any other animal. The Armor's Real Job: So what is the iron armor for? Defense against predators is the obvious guess, and it probably helps against grazing neighbors. But the leading hypothesis from biomechanical studies is that its primary role might be structural support. The composite, layered design of the sclerites may protect its soft foot from mechanical stress in the turbulent vent environment. It might also deter parasitic infections. It's a multi-purpose exoskeleton. Here's the gritty reality that most popular science articles gloss over: studying this snail is a logistical and financial nightmare. There is no casual observation. You need a multi-million dollar research vessel equipped with a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) like Jason or SuBastian. A single day at sea can cost over $50,000. The ROV dive to the vent takes hours just to descend. Then you have a few precious hours on the bottom. The manipulator arms must gently collect specimens into insulated, pressure-maintaining bioboxes for the ascent, which takes more hours. Even if you get a live specimen to the surface, keeping it alive for study is nearly impossible. The pressure change is fatal. Almost all research is done on preserved specimens or via in-situ experiments with landers placed on the seafloor. This is why progress is slow. We're piecing together the life of an alien creature from fragments, glimpsed during incredibly brief, expensive visits to its world. In 2021, the IUCN listed the scaly-foot gastropod as Endangered. Its entire range is estimated to be less than 0.02 square kilometers—the size of a few city blocks. The existential threat isn't climate change (directly) or pollution. It's deep-sea mining. The very hydrothermal vents it calls home are rich in copper, zinc, gold, and rare earth elements. Mining companies are actively exploring contracts to extract these polymetallic sulfides. A single mining operation could literally scrape an entire vent field—and every snail on it—off the map in a matter of days. The sediment plumes generated could smother adjacent vent communities. There's no way to mitigate this for a species with such a tiny, specific habitat. Conservation hinges on international regulation under the International Seabed Authority to create permanent, no-mining sanctuaries around known vent ecosystems like Kairei and Longqi. It's a political and economic battle playing out in meeting rooms, with the snail's fate as a key talking point. Can I keep a scaly-foot gastropod as a pet? Absolutely not, and this is a critical point many deep-sea enthusiasts misunderstand. The scaly-foot gastropod's entire existence is tied to the extreme conditions of deep-sea hydrothermal vents. The high pressure (250+ atmospheres), specific chemical cocktail (hydrogen sulfide, iron), and near-freezing ambient water are impossible to replicate in any home aquarium. Attempting to do so would be fatal for the animal within minutes. They are also an endangered species, making collection illegal. True appreciation for this creature comes from understanding its role in its natural, alien world. Does its iron armor protect it from all predators? It's not an impenetrable shield. The iron sulfide layers (greigite and pyrite) are brittle. Research suggests the armor's primary function might be structural support against the high-pressure deep-sea environment and possibly deterring some grazing predators, like other snails, by making the shell harder to rasp. However, it likely offers little defense against a determined crab's crushing claws. Its real survival strategy is a combination of this armor, its symbiotic bacteria that detoxify its environment, and the simple fact that its home is so hostile that few predators can even reach it. Why can't we breed them in captivity to save them from extinction? The challenge is monumental and goes beyond just pressure and chemistry. We lack fundamental knowledge about their life cycle. How do their larvae disperse in the vast, dark ocean to find a new, tiny vent site? What specific cues trigger settlement and metamorphosis? Without this, creating a captive breeding program is like trying to assemble a puzzle in the dark. Current conservation efforts are more focused on protecting their entire habitat from deep-sea mining, which is a more immediate and feasible target than replicating a 2.8-kilometer-deep, toxic, geyser-powered ecosystem in a lab.

Dive into the Iron Snail’s World

What is the Scaly-foot Gastropod?

Quick Snapshot: Scaly-foot Gastropod ID Card

Discovery: 2001, Kairei vent field, Indian Ocean

Depth: ~2,400–2,900 meters (~7,900–9,500 feet)

Key Feature: Iron sulfide (greigite/pyrite) sclerites & shell layer

Status: Endangered (IUCN Red List)

Diet: Chemosynthetic (via symbiotic bacteria)

How does the Scaly-foot Gastropod Build its Iron Armor?

The Big Misconception About the Iron

Life in an Extreme Real Estate Market

Vent Field

Location

Key Characteristics & Snail Population

Kairei Field

Central Indian Ridge

The discovery site. Vents here are iron-rich. This is thought to be the primary source population. The snails here have the classic black, iron-coated sclerites.

Longqi (Solitaire) Field

Southwest Indian Ridge

A more isolated site, discovered later. Fascinatingly, the scaly-foot gastropods here often lack the iron sulfide coating on their sclerites, which appear white. This suggests local geochemistry (lower iron?) influences armor formation.

Its Complete Survival Toolkit (It's Not Just the Armor)

The Brutal, Expensive Challenge of Studying It

A Future Hanging in the Balance: Deep-Sea Mining

Your Iron Snail Questions, Answered

The scaly-foot gastropod is more than a curiosity. It's a testament to life's ingenuity in the most punishing corners of our planet. It challenges our definitions of adaptation and reminds us that biodiversity isn't just about rainforests and coral reefs. The greatest wonders, and the most fragile, are often hidden in the dark, waiting to be understood before they're lost.

The scaly-foot gastropod is more than a curiosity. It's a testament to life's ingenuity in the most punishing corners of our planet. It challenges our definitions of adaptation and reminds us that biodiversity isn't just about rainforests and coral reefs. The greatest wonders, and the most fragile, are often hidden in the dark, waiting to be understood before they're lost.

The Iron Snail: Secrets of the Scaly-foot Gastropod's Armor

Comment