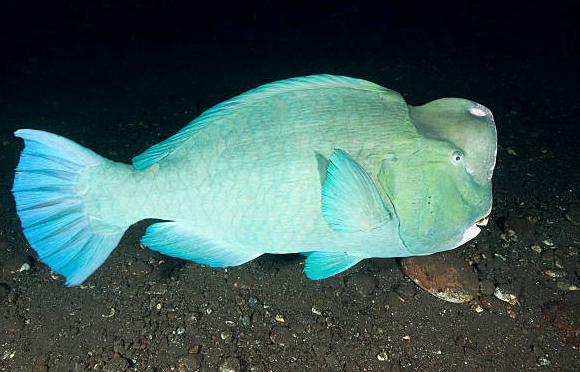

You're floating over a coral reef, the sun filtering down, when you hear it: a distinct, loud *crunch-crunch-crunch*. You look down and see a hulking, blue-grey fish with a bizarre bulbous forehead methodically biting chunks off a coral colony. That's Bolbometopon muricatum, the humphead (or bumphead) parrotfish. It's not just another colorful reef resident. This fish is a keystone species, an ecosystem engineer, and sadly, one of the most vulnerable giants in the ocean. Forget what you think you know about parrotfish – this one plays by different rules.

What's Inside This Guide

Biology & Behavior: Built Like a Bulldozer

Let's get the obvious out of the way. That forehead hump isn't for show. It's a bony protrusion that develops with age, and researchers from the Smithsonian Institution suggest it might be used for ramming coral to break off pieces, or even in head-butting contests with rivals. Think of it as a living battering ram.

They're the largest of all parrotfish, reaching over 4 feet (1.3 meters) and weighing up to 165 pounds (75 kg). They live long, slow lives – we're talking potentially 40 years or more. This longevity is a double-edged sword: it makes them wise to the reef, but also incredibly slow to recover from population declines.

Key Fact Check: The Beak That Eats Rock

Their fused teeth form a powerful, parrot-like beak. But here's a nuance most miss: they don't eat the living coral polyps for food. They're after the algae that grows on the dead coral skeleton. They ingest the whole chunk, digest the algae, and then excrete the pulverized calcium carbonate as sand. It's a full-time, reef-scale landscaping job.

Their life history is fascinating and complex. They are sequential hermaphrodites, starting life as females and some later transforming into large, terminal-phase males. These large males often lead spawning aggregations, a spectacular event where hundreds gather to release eggs and sperm. But these aggregations make them terrifyingly easy targets for fishermen.

Diet Through the Ages: A Changing Menu

Their diet isn't static. As they grow, their role on the reef shifts dramatically.

| Life Stage | Primary Diet | Ecological Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Juvenile | Filamentous algae, seagrass | Light grazing, minimal bio-erosion |

| Sub-Adult | Mixed algae & some live coral | Moderate grazing and sand production |

| Large Adult | Primarily live coral (Porties, Acropora) | Major bio-erosion, high sand production, controls fast-growing coral |

See that shift? A big humphead isn't just a bigger version of a small one. It's a different ecological actor entirely. Losing the big adults means you lose a specific, critical function that smaller fish can't replicate.

The Reef's Unsung Hero: More Than Just Sand

Everyone loves the "they make sand" fact. And it's true – a single large humphead can produce over 1,000 pounds of sand a year. That's the postcard fact. But their real value is grittier and less romantic.

They are the reef's primary bio-eroders. By constantly cropping fast-growing branching corals (like Acropora), they create space. This is vital. Without them, these fast-growers can dominate, creating dense, monolithic thickets that reduce habitat complexity and crowd out other coral species. The humphead's grazing promotes biodiversity, allowing slower-growing massive corals and other reef life to establish. It's like a giant, swimming gardener doing selective pruning on a colossal scale.

Furthermore, by breaking down old, dead coral, they accelerate the reef's nutrient cycling and sediment production, which is crucial for island building and beach maintenance. Studies in the Maldives and other atoll nations have directly linked healthy parrotfish populations to shoreline stability.

Threats & Conservation: A Fight for Survival

This is where it gets sobering. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the humphead parrotfish as Vulnerable, with populations declining globally. In some regions, it's considered Endangered or Critically Endangered. The causes aren't mysterious, but they are relentless.

- Overfishing: This is the big one. Their large size, predictable spawning aggregations, and tendency to sleep in shallow, accessible areas at night make them tragically easy to spear, net, or trap. They are prized for their meat in many parts of Asia and the Pacific.

- Habitat Degradation: Coral bleaching and reef destruction from climate change, pollution, and coastal development destroy their food source and home.

- Slow Life History: Their late maturity and slow growth mean that even if fishing stops today, recovery could take decades.

Conservation isn't just about putting up a "no fishing" sign. Effective protection requires a multi-pronged approach:

1. Species-Specific Protection: Generic marine protected areas (MPAs) help, but laws that explicitly ban the taking of humphead parrotfish are more effective. Countries like Fiji and the Maldives have implemented such bans.

2. Spawning Aggregation Protection: Identifying and rigorously protecting known spawning sites during aggregation periods is non-negotiable. This is where the bulk of the breeding population can be wiped out in a single night.

3. Tackling the Market: Reducing demand through consumer education and enforcing international trade restrictions under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) is crucial.

I've spoken with marine biologists in Palau who've seen night spearfishing decimate local populations. The consensus? Protecting the big, old humpheads isn't a luxury; it's essential surgery for the reef's health.

Diving & Encountering Them Responsibly

If you're lucky enough to dive where they still thrive – think remote areas of the Coral Triangle, parts of the Great Barrier Reef, or well-protected atolls in the Pacific – seeing one is a privilege. Here's how to be a good guest.

Listen first. You'll often hear that crunching before you see them. Stay calm, control your buoyancy (kicking up silt stresses corals), and observe from a respectful distance. Don't chase them. A startled humphead will swim off, wasting energy it needs to survive.

Respect the siesta. At night, they often sleep in shallow reef crevices or under ledges, enveloped in a protective mucus cocoon. Shining a bright light directly on them or touching them disrupts this vital rest period. Use minimal light and keep moving.

Choose dive operators and resorts that actively support local conservation efforts and adhere to responsible wildlife viewing guidelines. Your tourism dollars should support their protection, not their decline.

Your Quick Humphead Parrotfish FAQs

Can I keep a humphead parrotfish in my home aquarium?

How can I identify a humphead parrotfish while scuba diving?

Is the sand on tropical beaches really parrotfish poop?

What's the single biggest mistake people make about parrotfish conservation?

The humphead parrotfish isn't just a curious oddity. It's a barometer for the health of an entire ecosystem. Its decline signals a reef in trouble; its recovery, a sign of hope. Protecting this gentle, crunching giant means protecting the very structure and future of coral reefs themselves. Next time you walk on a white sand beach in the tropics, remember the unlikely engineer that helped put it there, and consider what we stand to lose if its crunch falls silent.

Comment